NOTE: This is a hypothetical research proposal created for a graduate-level Research Methods class. The paper isn’t perfect but thank you for wanting to read it! All my sources are linked at the end if you want to dive deeper into any of the topics.

Trafficking in Fear: Misinformation, Social Media, and the Real Victims of Sex Trafficking

by Georgia Laurette | November 2024

Introduction

On a seemingly ordinary evening, a woman posts a TikTok video recounting her brush with danger—a tissue stuck in her gas pump handle, allegedly a trafficker's lure. Her voice is urgent, her message clear: "Watch out." Within hours, her post is viewed millions of times, shared widely, and met with both skepticism and fear. Yet the story, like many others of its kind, has no basis in reality. (Fraser, 2022, p. 100) This phenomenon isn’t new; it is the latest chapter in a long history of trafficking-related conspiracies, updated for the TikTok era. There is not a hashtag or specific name related to this phenomenon yet, but it spreads and persists, nonetheless. My research explores the rise of sex trafficking misinformation on social media, particularly the visual and emotive storytelling on TikTok. I will do this in two phases, first, a long-term content analysis of people posting TikToks using #endtrafficking, #stoptrafficking, and #femalesafety. Followed by a snowball-sampling of the participants collected in the first phase to conduct in-depth interviews. In this study I seek to understand how such content distorts the reality of trafficking, who is making the posts, and how these narratives have evolved over time. I seek to understand more comprehensively who propagates these narratives. Though it is worth noting that I expect further questions will arise after the first phase of the research and that this section will be amended in the research process. For now, the research questions I seek to answer fall into two categories:

- Demographics Questions: Who are the content creators and engagers? What is their racial, religious, and geographic background? Are they primarily the victims in their stories or third-party narrators? Who shares the most and the earliest?

- Trends Over Time: How have these narratives evolved? What external factors (e.g., societal crises) influenced their rise?

To properly understand the specific phenomena I aim to study, I will start with the long history of moral sex panics that have already occurred in America and subsequently inform the modern moral panic that is the subject of this research. Starting in the early 1900’s with the “yellow peril” up through recent events like #Pizzagate and #SavetheChildren. Then I will move through the legal and policy impacts of these misinformation campaigns and how they are misused, followed by the direct impacts on victims. And end with the methodology behind my research.

Before we continue, it is important to discuss the complexity of the words I will be using to describe the people involved. Sex trafficking as defined by the Department of State “encompasses the range of activities involved when a trafficker uses force, fraud, or coercion to compel another person to engage in a commercial sex act or causes a person to engage in a commercial sex act.” While according to Mirriam-Webster dictionary prostitution is the act or practice of engaging in sex acts and especially sexual intercourse in exchange for pay, it is also noted that this is seen as an offensive and outdated term. Instead, the “the term sex worker has emerged as the preferred term of the global sex worker rights movement (Mitchell, 2022, p. 6).” But the line between sex trafficking victim, consensual sex worker, and prostitute is blurry and varies depending on who you talk to. As I reiterate throughout this paper, we should be centering the victim and survivors, so I will be using the terminology that they prefer. It is critical to recognize how the difference in terms and how they relate to perceived victimhood or risk, but also how they relate to receiving help or harm from the policies discussed. While a sex trafficking victim and a prostitute may appear indistinguishable to a police officer conducting a raid, they may need and want different forms of aid.

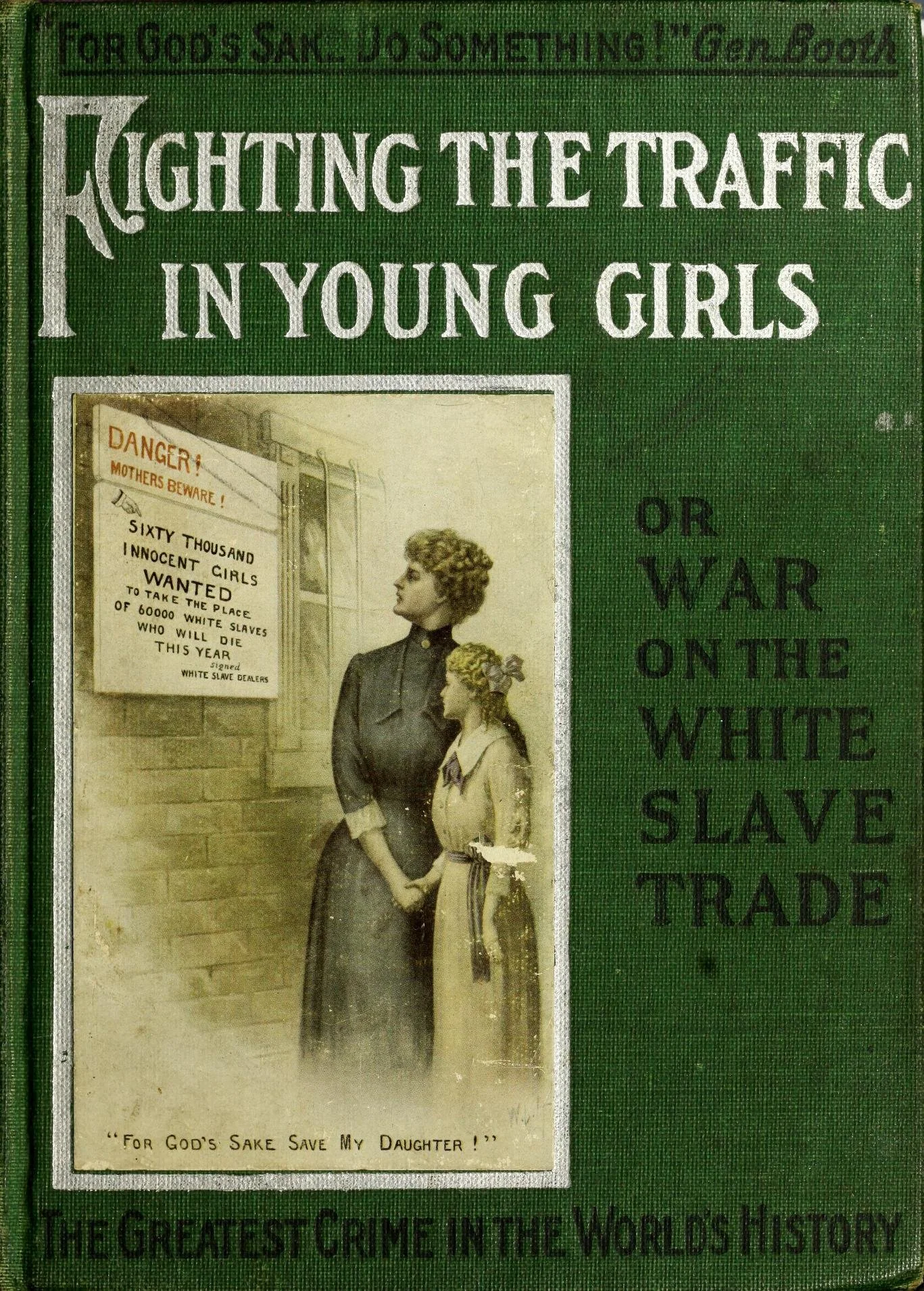

Cover of book published in 1911 by Bell, Ernest A. titled: “Fighting the traffic in young girls, or, War on the white slave trade”

Theoretical Framework

Historical Context: Moral Panics and the Long History of Trafficking Myths

In the early 1900’s large newspaper publishers like Hearst spread myths of young white women being drugged and tricked into a life of prostitution across the rapidly growing nation. Despite no evidence of the trafficking happening, this moral panic directly led to the creation of the Mann Act, or the White Slavery Act. This was a response to rapid changes in the industrial era like immigration and the evolving role of women (PBS, 2005) and was brought to congress in part by the KKK (Mitchell, 2022, p. 58). “The Mann Act made it a crime to transport women across state lines ‘for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose’ (PBS, 2005).” While on the surface it appeared to be legislation helpful to women in danger, it was instead used as a tool for blackmail and to punish other forms of sexual conduct not restricted to trafficking or even prostitution (PBS, 2005). “Such an interpretation of the law in effect criminalized all premarital or extramarital sexual relationships that involved interstate travel”(PBS, 2005). Instead of being used to protect the people it professed to keep safe, it was used as a tool to prosecute otherwise law-abiding people. It is important to note that this law was never repealed and is still on the books to this day although it has been modified slightly. This concept of white slavery and perceived victimhood that was institutionalized with the Mann act, became instilled in the minds of the American people as well as legislature to then be later recycled and referenced as fact in the coming decades. We will come to see that perceived victimhood is a recurring theme used to uphold white supremist ideals across American history through to the modern day.

In the ensuing decades there were moral panics around punk culture in Britain, the satanic panic, and hip hop, but the next directly related moral sex panic was called #Pizzagate. Culminating in 2016, #Pizzagate was a fringe online conspiracy theory involving DC pizzeria Comet Ping Pong and false allegations of political connections to child trafficking rings and other radical alt-right conspiracies (Rogers, 2020). “The Alternative Right, commonly known as the alt-right, is a set of far-right ideologies, groups and individuals whose core belief is that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “political correctness” and “social justice” to undermine white people and “their” civilization” (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2024). This conspiracy stayed in the fringes of the public zeitgeist and did not gain mainstream publicity until a man drove up to DC from North Carolina with an assault weapon to the shoot up the restaurant in a misguided attempt to save the fictional trafficked kids (Kennedy, 2017.) As defined by Britannica: conspiracy theory is an attempt to explain harmful or tragic events as the result of the actions of a small powerful group. Such explanations reject the accepted narrative surrounding those events; indeed, the official version may be seen as further proof of the conspiracy. #Pizzagate and the conspiracies surrounding it are still propagated today, though the movement has grown and shifted to combat efforts to suppress the misinformation they spread.

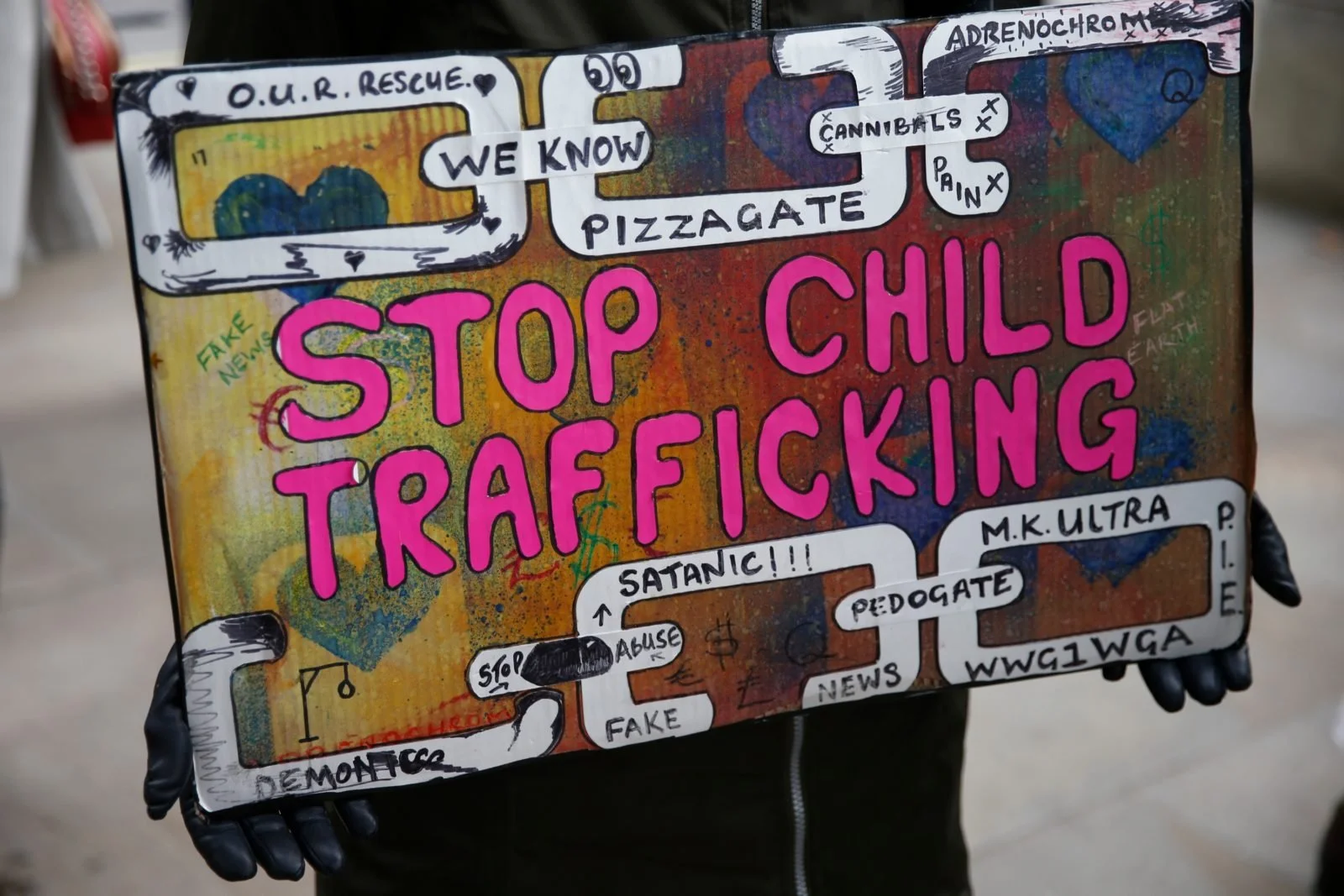

A protestor holds a sign during a “Save our Children” rally outside Downing Street in London, England. Conspiracy theorists have recently coopted #SaveTheChildren to find new followers.

Hollie Adams/Getty Images

Three year later, the next social media conspiracy theory #SaveTheChildren emerges, except this one made its way out of the far-right realm into the general population (Mitchell, 2022, Moran & Prochaska, 2023). This version of the conspiracy centered vaguely around a government officials trafficking children for sex trafficking and debunked claims of adrenochrome harvesting to supposedly extend the lives of the elite. This echoes descriptions of “immoral distribution centers” used to drum up fear during the creation of the Mann Act of the 1900’s (PBS, 2005). The growing attention towards #SavetheChildren was subsequently used by QAnon as a tactic to bring people over to their radical beliefs (Roose, 2020). Who can argue with saving children from sex trafficking? While you’re here, let’s expose you about these more extreme views like anti-semitism and white supremecy. QAnon support has shown up in the legislature in the form of elected politicians like Georgia congressperson Marjorie Taylor Greene and President Donald Trump, both of whom have expressed direct support for QAnon theories like #SavetheChildren (North, 2020). QAnon saw a 3000% growth in members after the virality of this hashtag (Mitchell, 2022) and resulted in a movie called “the Sound of Freedom” that centers around conspiracy theories of child sex trafficking rings and fictionalized stories of human trafficking, skewing reality and spreading misinformation (Bond, 2023). All this further distracting the public with misinformation and diverting resources from victims who genuinely need help. The fixation on a sensationalized story halts understanding of the real issue and a path to actually solving the issue (Johnston et al, 2014, p. 421). If everyone is distracted by a false story, there are fewer resources left to help actual victims, and as we will see, finding and helping these victims is often a very challenging task just by itself.

Four years after #Pizzagate, and the subsequent removal of QAnon content on social media, the latest moral panic focused on oddly priced furniture with girl names as the produt titles, on the online retailer Wayfair. Building on the fear and momentum of #SavetheChildren, and a general lack of public awareness of the connections with the far-right, #WayfairGate reached a larger audience than ever before, in spite repeated debunking of the conspiracy (Mitchell, 2022, p. 45). In an article by the Rolling stone article about this, #wayfair “…garnered 1.8 million total mentions, with 600,000 in a 24-hour period. By comparison, Wayfair had about 500 mentions a day prior to last week” (Dickson, 2020). A spokesperson for Wayfair told Reuters that the company uses an algorithm to name its products. The algorithm uses “first names, geographic locations and common words for naming purposes” (Reuters, 2020). Yet this clear answer only seemed to reinforce the conspiracy theorist and fueled theories online. While this hashtag helped to spread the conspiracy further, far right actors seized on the growing fear to convert a famously difficult audience to attract to their cause: women (Williamson et al, 2022). While other far-right ideas didn’t bring over female members, fear of sex trafficking and child trafficking was a highly successful tactic, which I propose is also happening in the subject I want to study.

Moral panics are not new. They are an unfortunate but integral part of the history of America and policies around sexuality and sex work, from the Mann act of 1910 to #Pizzagate, #Wayfairgate, and the new phenomena brewing now that I propose to study. They have shaped the public understanding of human trafficking, regardless of the accuracy, as well as shaped policies on sexuality with ripple effects still seen today. As we will see, there are lasting impacts to this kind of misinformation making its way into public policy that impact far more than just the people they aim to help, often in a negative way.

The Problem: Misinformation’s consequences

While at first glance, trafficking conspiracies might seem harmless or even well-intentioned, but they carry serious and lasting repercussions. Perhaps the most visible impact is on policy and how laws are created based on misinformation and the dangers that this entails. Then I will explore the consequences of all the attention being focused on a false report. If all the resources are spent looking for fictious victims, who is there to save the real victims? Finally, we will look into the harm caused to genuine trafficking victims when their story doesn’t follow the sensationalized pattern seen in these melodramatic retellings.

Laws like SESTA/FOSTA, the SAVE Act and the MANN Act, while at the surface aimed at trafficking prevention, in fact disproportionately harmed consensual sex workers, pushing them into more precarious circumstances. Likewise, exaggerated numbers of human trafficking may result in unwise policy decisions (Johnston et al, 2014, p. 421), and then those inaccurate numbers are recycled and reused until they have no significance but are referenced everywhere as true.

The Mann Act was ostensibly created to protect vulnerable young women from being lured into the immoral forms of work. Specifically, it outlawed crossing state lines for prostitution, but after failing to find these white slavery cabals, they turned instead to use the law to punish people in extramarital affairs or as a tool of blackmail instead of the intended purpose of saving women from sex trafficking (PBS, 2005; Mitchell, 2022). It is important to note that the Mann Act was never repealed, instead it has been minorly updated over the years and is still on the books. SESTA/FOSTA emerged as an attempt to stop sex trafficking on online marketplaces like Craigslist or Backpages by punishing the website for hosting ads implied to be ads trafficking women (Armbruster et al, 2020). Yet instead of helping the victims, or prosecuting the traffickers, the law simply penalizes the website for hosting the ads. This resulted in websites like Craigslist completely shutting down advertisement of sex workers and pushing them to alternative and less safe methods of advertising (Hamilton, 2016). Also subsequently pushing them to more public forms of advertisement like on TikTok or Instagram where previously they did not need to be in order to generate business. Next is the SAVE act, another similar law that aimed to protect minors but instead results in all the same issues as the previous two examples. It is yet another inherently flawed legislation created on the back of yet another moral panic (Hamilton, 2016, p. 433). That once again fails to save victims and instead cause collateral damage in their wake, meanwhile leaving the actual traffickers to flourish often without any recourse.

Viral claims around sex trafficking result in a marked increase of false reports which flood authorities and divert attention from real trafficking cases (Rogers, 2020). According to the Polaris Project, the extreme influx of false reports due to the viral #WayfairGate made it significantly more difficult to provide support and attention to the real people in need. The mainstream but still rooted in conspiracies and surrounded by QAnon supporters, Sound of Freedom is a movie released in 2023 about a fictionalized story of child sex trafficking, but yet again this created a moral panic around a situation that wasn’t in fact happening, yet again diverting funds and attention from the people who need it (Bond, 2023).

Although huge numbers like 400,000 women and girls are trafficked annually (Statista, 2017) float around the zeitgeist and have for decades, there is little to no empirical data behind these numbers (Mitchell, 2022). At this point they exist more to prop up previous examples using the number and to continue funding efforts (Mitchell, 2022). Yet these false reports continue to circulate and are used by far-right conspiracy theories to prop up their own more extreme ideas.

The sensationalized depictions in these conspiracies make it harder for victims to recognize their experiences as trafficking, especially when their stories don’t match the media narrative. While there is no singular description for a trafficking victim, there are a set of factors that are known to increase the chance that someone becomes a victim of trafficking: child abuse, domestic violence, family history of alcoholism, poverty, and immigrant status are all factors that make someone more likely to become a victim of trafficking (Twis, 2020; UNICEF, 2024; Department of State, 2024). But none of that is jazzy or exciting, it is sad and alarmingly prevalent. So, when the trafficking doesn’t involve bags over the head or getting drugged and kidnapped, but instead emotionally manipulated, it is easy for the victim to blame themselves instead of the trafficker and end up not recognizing or reporting that they were trafficked. If a victim is convinced that they are a prostitute and thus against the law, they become dramatically less likely to report incidences of rape or abuse, let alone trafficking.

While these conspiracies revolve around fabricated versions of trafficking, we have to remember that there are still genuine examples of trafficking that get overlooked, often because there isn’t this perfect victim to parade around for the media. (Johnston et al, 2014; Campbell, 2016). Meanwhile evidence abounds of the benefits of centering real survivors’ stories to media, policy, public awareness, and empowerment to the victims directly (Johnston et al, 2014, p. 431). While it can be understandably difficult to obtain stories from genuine victims, it is imperative that we focus on them and their experiences to create better, more effective policies.

Each of these laws, the Mann Act, SESTA/FOSTA, the SAVE act and, were founded on moral panics around the over-exaggerated sex trafficking of women. But instead of saving these victims, the laws instead harm consensual sex workers and average people. They have fueled a centuries long panic rooted in white supremacy and xenophobia meanwhile never helping the genuine victims of trafficking. If people and legislators are distracted trying to solve a nonexistent problem, there are no resources left to help the people who really are in danger.

Methodology: A Two-Phase Analysis

Phase One: Content Analysis

In the first phase of my methodology, I will conduct a quantitative content analysis of TikTok videos using hashtags #EndTrafficking and #FemaleSafety from January 2014 – January 2024. I selected TikTok because previous research (Williamson et al, 2022) has investigated a similar conspiracy on Twitter but suggests that valuable information would be obtained with a more visual social platform. Instagram or TikTok would work equally well but the algorithm behind TikTok is more robust and appears to draw in a wider range of people, thus being more valuable as an entry to the alt-right pipeline. I selected this timeframe because it should contain time before this specific phenomenon emerged but would also encompass the other viral conspiracies mentioned in this paper. The duration of the study needs to be long-term in order to capture changes in who is posting and any connections to policy changes or potential judicial action. I selected these two hashtags because they overwhelmingly contain videos that fit the nebulous description for the phenomena I want to study: first person POV videos made on cell phones describing suspected attempts of human trafficking. Because there is not a specific hashtag associated with this latest moral panic, I selected hashtags that I knew would encompass the conspiracy videos, but also likely have genuine informative content that will inevitably get drowned out by misinformation.

In my data collection I will look for demographic patterns, recurring themes, and shifts in storytelling techniques. Some variables I plan to track include age, race, location, gender, language, recurring terminology in captions, as well as recurring participants involved in the conversation (Moran & Prochaska, 2023). I anticipate this list will grow and shift as research is conducted and new information evolves about the people involved in these posts. Once data collection is finished, I will work with a team to achieve inter-coder reliability in multiple rounds (Twis, 2020; Johnston et al, 2014). This will require a large team as I expect a significant amount of data will be collected in the first phase that will need to be coded and organized so we can contact the participants in the next phase of the research.

Due to the sensitive nature of the content, we are studying, proper data protection and anonymity will be crucial. Data will only be associated with names for the initial collection process and the survey phase, after that the master file connecting the names and information will be deleted to ensure anonymity.

Phase Two: In-Depth Interviews with Sample of Creators and Engagers

Now that we have an idea who is generating and interacting with these posts, as well who the advocates and survivors are, I will use that information to engage them through in-depth interviews. Through interviews I will be able to ask questions and question-lines otherwise impossible through other collection methods like content analysis or a survey. At this point I know who these people are, what they talk about, and likely have strong guesses about their demographic profile, but I want to hear what these participants think in their own voice. Are the questions I asked in the first phase confirmed or denied by the interviews? Have their thoughts and opinions changed over time? Do they still agree with what they posted?

In the process of conducting the content analysis I will already have a long list of accounts and contact information, but in order to gain the tryst of the account holders I wish to interview, a snowball-sampling process can facilitate entry into the social network I wish to study. The definition of snowball-sampling “is as a sampling method in which one interviewee gives the researcher the name of at least one more potential interviewee. That interviewee, in turn, provides the name of at least one more potential interviewee, and so on, with the sample growing like a rolling snowball if more than one referral per interviewee is provided” (Kirchherr et all, 2018).

I will begin with sending out emails and direct messages to first group of accounts, starting with the most active and vocal accounts discovered in phase one. These would be the most likely to be actively checking messages while also likely to be in communication with other accounts I’m trying to engage, to potentially discuss the arrival of the messages and spread the likelihood of further involvement in the study. This social network could also communicate amongst each other after the interviews begin, further strengthening the trust of the interviewer and potential interviewees. The outreach process will be repeated in waves to increase likelihood of engagement with new participants, building on the momentum of interviewees discussing the study and the interview process.

While in-person interviews would be optimal, the lack on restrictions to location that happen in online social networks require that the interviews be conducted virtually through a medium like Zoom or Skype. I expect to come into this phase of the research with some expectation of where the population I am studying is located, but I also expect that they will be spread across the country. It may be beneficial to conduct select interviews in person to further strengthen trust within the growing network of interviewees.

My potential interview questions fall into three groups: background, perception of trafficking, engagement with conspiracies, community influence, reflections on impact, demographic insights, and future actions. Erach of these categories build on concepts developed throughout my theory and offer an opportunity to confirm or deny that information with direct feedback from the people propagating these conspiracy theories. Some potential questions: What do you hope viewers learn from your posts; what are the main signs of trafficking; have your views about trafficking changed since you began posting; how has the online community shaped your views since posting; and how do you see your role in combatting trafficking going forward?

Next Steps: Judicial Comparison

Further research can tie this work into the impact that it has on survivor reporting and I lay below some suggestions for how this may begin. I suggest examining federal and state judicial records to identify trends in trafficking reports, arrests, and convictions, correlating them with spikes in conspiracy content (Twis, 2020). The analysis would cover the entire US federal and state judicial records of sex trafficking including reports, arrests, and convictions from the same time frame as the content analysis: January 2014 - January 2024. Admittedly this is a wide net of information but there are no geographical constraints on the population from the previous two phases so there should be as little constraint on this phase as possible while still maintaining a reasonable approach and methodology. Perhaps future research can attempt to compare this information on a global scale, but I will only attempt to achieve an American perspective of the issue at hand. I will then conduct multiple regression analyses to discover patterns within the data, looking particularly for spikes around the conspiracies but also arrests and convictions related to those conspiracies. I suspect there will be a high number of false reports around these frenzies but with no comparable rise in arrests or convictions due to the false nature of the reports.

Conclusion

From the Mann act to SESTA/FOSTA, the yellow peril and #WayfairGate, the premise is the same: co-opt a fear around victimized women and use it to punish the poor and under-privileged. These ideas then get entrenched in policy and re used to support further policy measures, despite the shaky ground of the initial law.

My research is done in two phases with suggestions for future research topics to further explore this subject. Starting with a long-term quantitative content analysis to understand who is spreading this conspiracy and locate any trends in how the discussion is changing over time. Followed by in-depth interviews of a sample of the participants collected in the first phase to confirm/deny suspicions on demographics and to attempt to understand their opinions and ideas otherwise unattainable through content analysis alone. I then suggest how further research could like this into the impact that it has on genuine sex trafficking victims. This is done through a quantitative analysis of the judicial records related to sex trafficking to see if there is a negative impact on real victims, due in part to distracted resources. My hope in conducting this research is generate information to inform better policy that center’s survivors and action over misinformation and melodrama.

Bibliography

Albert, K. (2021). FOSTA in legal context. Columbia Human Rights Law Review. 52(1), 1084-1159

Beutin, L. P. (2023). Trafficking in Antiblackness : Modern-Day Slavery, White Indemnity, and Racial Justice. (1st ed.). Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478024354

Bond, S. (2023, July 20). Christian thriller ‘Sound of Freedom’ faces criticism for stoking conspiracy theories about child trafficking. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/07/20/1189066585/christian-thriller-sound-of-freedom-faces-criticism-for-stoking-conspiracy-theor

Dickson, E. J. (2020, July 15). Wayfair child trafficking conspiracy theory spreads on TikTok. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/wayfair-child-trafficking-conspiracy-theory-tiktok-1028622/

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Conspiracy theory. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/conspiracy-theory

Fraser, C. (2016). An analysis of the emerging role of social media in human trafficking: Examples from labour and human organ trading. International Journal of Development Issues, 15(2), 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJDI-12-2015-0076

Hamilton, L. (2016). Sex trafficking legislation under the scope of the harm principle and moral panic. Hastings Law Journal, 67(2), 531-564.

Hauck, G. (2017, June 22). Pizzagate conspiracist sentenced to prison for shooting at D.C. pizza restaurant. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2017/06/22/politics/pizzagate-sentencing/index.html

Hupp Williamson, S., Creel, S., & Walker, E. (2023). WayfairGate and the Growth of Sex Trafficking Panics Across Social Media. Critical Criminology (Richmond, B.C.), 31(3), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-022-09677-2

Johnston, A., Friedman, B., & Shafer, A. (2014). Framing the Problem of Sex Trafficking: Whose problem? What remedy? Feminist Media Studies, 14(3), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2012.740492

Kirchherr, J., Charles, K., & Guetterman, T. C. (2018). Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PloS One, 13(8), e0201710–e0201710. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201710.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Prostitution. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/prostitution

Mitchell, G. (Gregory C. (2022). Panics without borders : how global sporting events drive myths about sex trafficking. University of California Press.

North, A. (2020, September 15). How #SaveTheChildren is pulling American moms into QAnon. Vox. https://www.vox.com/21436671/save-our-children-hashtag-qanon-pizzagate

PBS. (n.d.). The Mann Act. Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/unforgivable-blackness/mann-act

Polaris. (2020, July 15). Polaris statement on Wayfair sex trafficking claims. Polaris Project. https://polarisproject.org/press-releases/polaris-statement-on-wayfair-sex-trafficking-claims/

Reuters. (2020, July 10). Fact check: No evidence linking Wayfair to human trafficking operation. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-factcheck-wayfair-human-trafficking/fact-check-no-evidence-linking-wayfair-to-human-trafficking-operation-idUSKCN24E2M2/

Rogers, K. (2020, August 20). QAnon’s obsession with #SaveTheChildren is making it harder to save kids from traffickers. FiveThirtyEight. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/qanons-obsession-with-savethechildren-is-making-it-harder-to-save-kids-from-traffickers/

Roose, K. (2020, August 12). QAnon’s latest plot: 'Save the Children' campaign attracts mothers. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/12/technology/qanon-save-the-children-trafficking.html

Southern Poverty Law Center. (n.d.). The alt-right. Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/alt-right

Statista. (n.d.). Number of victims identified related to human trafficking worldwide by region. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/459646/number-of-victimsidentified-related-to-human-trafficking-worldwide-by-region/

Twis, M. K. (2020). Predicting Different Types of Victim-Trafficker Relationships: A Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis. Journal of Human Trafficking, 6(4), 450–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2019.1634963

UNICEF USA. (n.d.). Child trafficking. UNICEF USA. https://www.unicefusa.org/what-unicef-does/childrens-protection/child-trafficking#:~:text=National%20Human%20Trafficking%20Hotline%20statistics,victims%20of%20child%20sex%20trafficking.%20

U.S. Department of State. (2024). 2024 Trafficking in Persons report: United States. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/united-states/

U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). About human trafficking. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/humantrafficking-about-human-trafficking/

Valianatos, C. (2023). Sex Trafficking in the Media: How U.S. Newspapers Narrate This Social Issue.